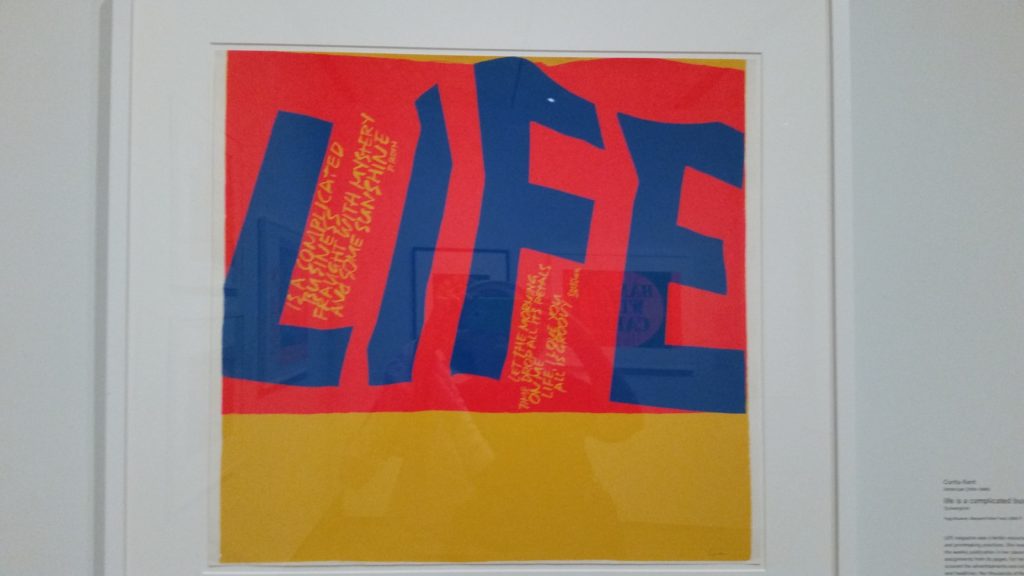

Having just published a book on the late 1960s, and having driven past the famed Corita Kent gas tanks on route 93 South of Boston hundreds of times, I wondered, on entering the wonderful new exhibit “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” at the Harvard Fogg Museum how I could possibly have missed Kent’s amazing presence in the Pop Art scene.

Having just published a book on the late 1960s, and having driven past the famed Corita Kent gas tanks on route 93 South of Boston hundreds of times, I wondered, on entering the wonderful new exhibit “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” at the Harvard Fogg Museum how I could possibly have missed Kent’s amazing presence in the Pop Art scene.

The show juxtaposes some 60 works by Kent–who was born in 1918 and became a nun in 1936–with approximately the same number of works by known pop figures such as Andy Warhol, Jim Dine, Edward Ruscha, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Indiana, and others. It examines Kent’s screen prints; that 1971 bold “rainbow swash” design for the Boston Gas tank, as well as films, books, and other works.

But in a talk after the September 3 opening, Susan Dackerman, consultative curator of prints at the Harvard Art Museums, said that she herself had not known much about Kent’s work until she met another curator’s sister–Mary Anne Karia (née Mikulka), a former student of Kent’s at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, and a long-time friend of Kent’s. Mikulka showed Dackerman the notes, papers and prints saved from her student and later days. That introduction, in 2010, turned into a multi-year research project in which a team of Harvard art historians and graduate students began to place Kent–who left the convent and moved to Boston in 1968– in the artistic and cultural movements of her time.

The exhibition explores how Kent’s work both responded to and advanced the concerns of Vatican II, a movement to modernize the Catholic Church and make it more relevant to contemporary society. The church advocated conducting the Mass in English. Kent, like her pop art contemporaries, simultaneously turned to vernacular texts for inclusion in her vibrant prints, drawing from such colloquial sources as product slogans, street signs, and Beatles lyrics. Vatican II also advocated having priests turning to face their congregants–a theme shown in the reversals of words in various Kent prints which require viewers to commune or relate to the work in new ways, as pointed out by Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities. While Kent questioned the authority of the Church, she also took up the church’s fight against poverty as an artistic theme.

require viewers to commune or relate to the work in new ways, as pointed out by Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities. While Kent questioned the authority of the Church, she also took up the church’s fight against poverty as an artistic theme.

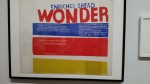

By bringing “Wonder Bread” into her work, according to American studies graduate student Eva Payne Kent, Kent pointed out the need for food and the leavening qualities of bread–as well as the symbolism of the communion wafer, and the sharing of bread as a means of communion among everyday people.

By bringing “Wonder Bread” into her work, according to American studies graduate student Eva Payne Kent, Kent pointed out the need for food and the leavening qualities of bread–as well as the symbolism of the communion wafer, and the sharing of bread as a means of communion among everyday people.

Kent thus emphasized the egalitarian rather than the authoritarian, and, unlike the implied messages of recognized pop artists, her messages made her art not purely critique of the commercial world but brought out the importance of quotidian life.

In 1968, a year after she was featured as the new nun on cover of Newsweek Magazine, Kent left the convent and her teaching position and moved to Boston.

At this point, as sixties political protests escalated, Kent began to include news photo images of war, racial struggles, political figures in her prints– perhaps relying less on words to express emotion. I fo und these works less vivid–but they packed a punch-. I was especially taken by an anti-war print that included a photo of Daniel and PHilip Berrigan, friends of hers who were priests and antiwar activists with whom I interacted at Cornell and later, during the Trial of the Harrisburg 8.

und these works less vivid–but they packed a punch-. I was especially taken by an anti-war print that included a photo of Daniel and PHilip Berrigan, friends of hers who were priests and antiwar activists with whom I interacted at Cornell and later, during the Trial of the Harrisburg 8.

Asked in Q&A why Kent had not been considered important to the Pop Art, Dackerman pointed out that a center of the movement had been the Ferris Art Gallery, in Los Angeles–and that the recognized pop artists were often referred to as the “Ferris Studs.” Not only was she a woman, Dackerman said, but she was, of all things “a nun.”. Another speaker mentioned that unlike her male counterparts, Kent, then called “Sister Mary Corita,” might have been considered “too cheery” and positive about the Church, possib ilities for communion, and the egalitarian nature of the commercial world.

ilities for communion, and the egalitarian nature of the commercial world.

All in all–the show is a must-see for anyone interested in the 1960s, pop art, female artists or the relationship of art, religion, politics and social change.,

Anita M. Harris

Anita Harris is the author of Ithaca Diaries, Coming of Age in the 1960s and of Broken Patterns, Professional Women and the Quest for a New Feminine Identity.

Print and e-versions of both books are available on Amazon or Kindle.

New Cambridge Observer is a publication of the Harris Communications Group, an award-winning PR and marketing firm in Cambridge, MA.