Georgia O’Keeffe Inspirational at the Peabody Essex

Still thinking about the fabulous Georgia O’Keeffe show I saw last Sunday at the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, MA. “Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style,” is a retrospective going back to O’Keeffe’s high school years. It continues through her experiences in Chicago, Texas, New York City, Lake George, New Mexico and beyond her lifetime, to the present day.

Still thinking about the fabulous Georgia O’Keeffe show I saw last Sunday at the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, MA. “Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style,” is a retrospective going back to O’Keeffe’s high school years. It continues through her experiences in Chicago, Texas, New York City, Lake George, New Mexico and beyond her lifetime, to the present day.

The exhibit features not only her art work through those years, but also year-book entries, photos of and by O’Keeffe, video of a conversation in which she says she was lucky that her work coincided with her time and was liked but that her paintings might have been better if she’d remained unknown.

Central to the show is the distinctive clothing she designed and wore–presented in relation to her paintings.

Central to the show is the distinctive clothing she designed and wore–presented in relation to her paintings.

The show includes video from a 2018 fashion show in which models prance on a runway. wearing styles like those originated by OKeefe.(immediately below)

My friend E remarked on O’Keeffe as a feminist force. But while O’Keeffe was a ground breaker in the art world and is sometimes referred to as “the mother of abstract art,” a PEM commentary points out that she insisted throughout her career that she did not want to be considered a female artist…but simply an artist.

I did wonder what would have happened if famed New York City photographer Alfred Stieglitz, 30 years her senior, had not seen her work when she was a young artist and championed it–and her; if she had not moved to New York and married him; if he had not taken and shown photograph after photograph of her; if she had not had the safety and freedom afforded by Stieglitz and his family wealth in NY and Lake George. But an example of the early commercial artwork (left), on which she embarked to supplement her Texas teaching salary, makes me certain she would have become renowned on her own.

But an example of the early commercial artwork (left), on which she embarked to supplement her Texas teaching salary, makes me certain she would have become renowned on her own.

While I love most of O’Keeffe’s paintings, I’m less enamoured of her fashion, which the show presents as an element of her artwork. In my view, it seems to have become more traditionally masculine–with chunky-looking black suits ordered from a men’s clothier in Hong Kong– as she moved on in life.(Or, as women’s societal roles changed?)

I’ve seen quite a few O’Keeffe shows over the years..several in New York, and one in Glens Falls, NY, near Lake George– but this is the first I’ve seen that incorporates and integrates so many aspects of her life.

I would have liked to have been told a bit more about O’Keeffe’s childhood and family and about her relationship with Stieglitz, but then, there’s Wikipedia for that. All in all, I found the exhibit of an artist who worked well into her 90s enriching and inspirational.

- New YorK City

- Lake George

- New Mexico

Should also mention the wonderful docent and ceramic artist/jewelry maker who told me that the unlabelled photos were taken by O’Keefe and encouraged me and other visitors to share our comments and photos on Instagram. Also, btw, the PEM cafeteria serves the richest, thickest hot chocolate I’ve ever tasted.

–Anita Harris

Anita M. Harris is a writer, photographer and communications consultant basedin Cambridge, MA. She is the author of Ithaca Diaries, Coming of Age in the 1960s, and Broken Patterns: Professional Women and the Quest for a New Feminine Identity.

New Cambridge Observer is a publication of the Harris Communications Group, a PR and content marketing firm based in Kendall Square. :

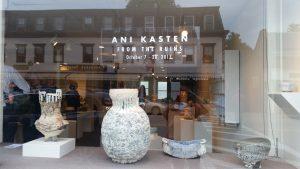

According to a gallery publication, Kasten was drawn to the medium of clay as an apprentice to British ceramist Rupert Spira, Then she headed a stoneware making facility in Nepal for four years before returning to the USA to set up ceramic studios in California, Maryland and most recently Minnesota. She has exhibited her work nationally and internationally with works in the permanent collections of the Racine Art Museum, Wisconsin; the Weisman Art Museum Minneapolis MN; and the Sana’ a Collection, the US Embassy, Sana’ a Yemen.

According to a gallery publication, Kasten was drawn to the medium of clay as an apprentice to British ceramist Rupert Spira, Then she headed a stoneware making facility in Nepal for four years before returning to the USA to set up ceramic studios in California, Maryland and most recently Minnesota. She has exhibited her work nationally and internationally with works in the permanent collections of the Racine Art Museum, Wisconsin; the Weisman Art Museum Minneapolis MN; and the Sana’ a Collection, the US Embassy, Sana’ a Yemen.

Through the Looking Glass is a 40-year retrospective of the Washington State artist’s blown glass sculptures–such as a boat containing thousands of glass flowers, fantastical forests, sculptures based on South American basketry–which took us out of our doldrums and got our imaginations flowing and reminded us that we can each create worlds of our own.

Through the Looking Glass is a 40-year retrospective of the Washington State artist’s blown glass sculptures–such as a boat containing thousands of glass flowers, fantastical forests, sculptures based on South American basketry–which took us out of our doldrums and got our imaginations flowing and reminded us that we can each create worlds of our own.

In

In