In photos of Harvard Square from the Covid 19 pandemic, , Anita Harris shows the ongoing transformation...

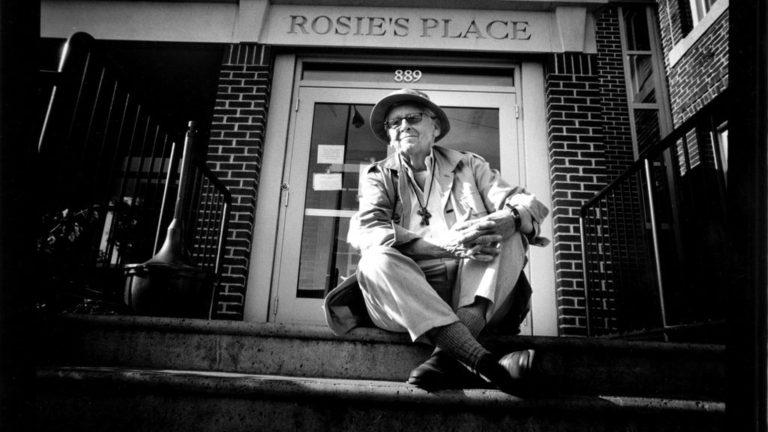

Anita M. Harris

Lacoste ceramics Gallery in Concord features eight artists of color in response to the current cries for...

New Cambridge Observer's Anita Harris writes that the free press--alternative or traditional--can make a huge difference in...

Writer Anita Harris is thankful that Cambridge has reached phase 3 in Massachusetts' covid reopening --and...

Anita Harris on Lacoste, Concord Gallery opening of Lily Fein response to George Ohr, 19th Century...

Cambridge writer Anita Harris explains Covid 19 mask requirements in Cambridge, Watertown, and in other Massachusetts communities,